It is hard to establish a context for a miscellaneous collection of sayings such as one finds in the center of Proverbs. But the text clearly divides it into the four main sections shown below:

Figure 1: The Central Section of Proverbs

I. Solomon’s Proverbs: Part I (10:1-22:16)

A. Proverbs of Contrast (chs. 10-15)

B. Proverbs of Comparison (16:1-22:16)

II. Book of Wisdom: Part I (22:17-24:22)

II''. Book of Wisdom: Part II (24:23-34)

I'. Solomon’s Proverbs: Part II (chs. 25-29)

B. Proverbs of Comparison (chs. 25-27)

A. Proverbs of Contrast (chs. 28-29)

The two collections of Solomon's adages probably circulated separately and do contain several duplicated or near-duplicated sayings. For example, just within Proverbs 14 we have the following:

14:1 // 29:4

14:17,29 // 29:11

14:23-25 // 28:21

14:31 // 29:13

Note that all of these parallels are found in the two sections labeled “Proverbs of Comparison.” The technical name for the form this type of proverbs takes is “antithetic parallelism.” A simple contrast is set up in the two lines of poetry found within each verse:

“A is X, but

B is Y.”

There are a surprising number of such contrasted pairs A and B in Proverbs 14, including wise and foolish, faithful and false, fools and the upright, wicked and righteous, joy and grief, perverse and good, simple and clever, poor and rich, toil and talk, truth and lies, tranquil and emotional, and righteousness and sin.

As to how all these individual proverbs are arranged within the book: “The sayings in chs. 10-22 show little continuity, and scholars are still groping to discern reasons for their sequence in the text.” (LaSor) Dorsey echoes this negative assessment and even extends it to the section labeled I' above. There may be no detailed organization to the order of these Solomonic proverbs, but Murphy has demonstrated the extensive use of catchwords to connect adjacent sayings in the first collection (Section I). Skehan even sees significance in the fact that this section contains exactly 375 proverbs since the Hebrew word for “proverb” has a numerical value, using gematria (i.e. a common mystical Jewish practice of adding up the numbers associated with the letters in a word to obtain hidden meanings), of 375.

Translation Issues

This chapter suffers from a number of translation problems in at least 14 verses out of the 35. Perhaps this can be attributed to the early age of the writings and the use of archaic words even at the time of writing. Here are brief discussions of some of these problem verses:

Proverbs 14:1

The Hebrew text makes no sense grammatically: “The wisest women builds a house.” Therefore we have “Wisdom builds herself a house (RSV, JB)” by deleting “women” in order to bring it in line with the parallel wording in Proverbs 9:1a (“Wisdom has built her house.”) NRSV merely corrects the grammar to “The wise woman builds a house.” Alternatively, Hulst suggests “the wisdom of the women.”

Proverbs 14:3

The Hebrew reads, “The talk of fools is a rod of pride (ga'awh).” RSV reads the Hebrew as gewo(h) (“back”) instead. NIV makes a similar adjustment, which C.G. Martin rejects as being unsupported in the text. However, Hulst notes that such a change would bring the thought in line with that of Proverbs 10:13.

Proverbs 14:4

Whybray states that “the Hebrew here is obscure...the point may be that the farmer has to balance the grain consumption of the ox with the value of the work which it does; and if he does so he will realize that it is well worth the expense.”

Hulst similarly says, “The translation of this word is not certain.” But he sees a possible pun since bar can mean either “corn” or “clean.” “Thus, he asks the question, 'where there are no cattle, does one expect to find there any corn (bar) in the manger? The answer is 'of course not,' for one expects to find in that case, a manger that is clean.”

By contrast, RSV changes 'ebus (“manger”) to 'epes (“nothing”) to get “where there are no oxen, there is no grain.”

Proverbs 14:9

Walls reads the obscure first line of this verse as “Guilt(-offering) mocks at fools.” He feels that this “might mean that the sacrifices offered for sin mocks them by their ineffectiveness..., but it seems a curious way to express it...the translation of this difficult verse remains tentative.”

Hulst: “The sense of the sentence is somewhat vague, though it seems to mean that, because fools offer the guilt offering so often and so carelessly it becomes a mockery to them. But 'asam also means 'guilt', and this may be its sense here...The RSV has adopted a completely different reading eliminating any mention of 'guilt.' It renders, 'God scorns the wicked.'”

Whybray states, “The whole of this verse is difficult. The N.E.B. translation represents only one of the possible guesses at its meaning.” That rendering reads, “A fool is too arrogant to make amends; upright men know what reconciliation means.”

C.G. Martin also states that NIV, RSV, and NEB are all guessing at the meaning of the Hebrew text. “There is, however, a good case for AV 'Fools make a mock of sin'...”

Proverbs 14:14b

Hulst explains that RSV changes the Hebrew word ume'ala(y)w to umimma'lala(y)w to yield “and a good man with the fruit of his deeds” in an attempt to provide a better parallel thought to the first line of the verse.

Proverbs 14:17b

Several commentators note that this verse can be taken in one of two ways depending mainly on whether the Hebrew word mezimma(h) is taken to be positive (“discretion”) or negative (“deviousness”).' Thus, the Hebrew reads: “a man of careful thought is hated.” As Whybray states, “This makes no sense.” Thus, NEB translates this line as “distinction comes by careful thought” by just a slight change in the Hebrew text. Others somewhat similarly render it as “a man of discretion is patient.”

One factor in favor of this altered wording is the fact that most of the proverbs in Proverbs 14 consist, as stated above, of two lines in which there is a contrast rather than a comparison between them. That alone would seem to argue against any understanding of verse 17 such as we see in NRSV:

“One who is quick-tempered acts foolishly,

and the schemer is hated.”

Instead an antithetic translation such as in The Jerusalem Bible would seem to be preferable:

“A quick-tempered man commits rash acts,

(but) the prudent man will be long-suffering.”

Proverbs 14:24b

J. Davies sees no problem with the Hebrew text as it stands since “folly is both a cause and a result of being a kesil, most notably Proverbs 14:24: 'the folly ['iwwelet] of fools [kesilim] yields folly ['iwwelet].”

However, others think that this makes no sense whatsoever and thus change the Hebrew wording slightly to come up with alternative translations such as:

“Folly is the chief ornament of the stupid.” (JB)

“Folly is the garland of fools.” (RSV, NRSV)

Proverbs 14:32b

This is a rather important verse theologically, but unfortunately there is a controversy concerning the actual wording. The King James Version (AV) of the whole verse reads:

“The wicked is driven away in his wickedness:

but the righteous has hope in his death.”

Bruce Waltke gives the fullest explanation of the problem in the second line: “The restoration of the original OT text is foundational to the exegetical task and to theological reflection. For instance, whether the book of Proverbs teaches immortality depends in part on deciding between textual variants in Prov. 14:32b. Basing itself on MT [the Hebrew text], the NIV renders, 'even in [their] death (bemoto) the righteous have a refuge,' a rendering that entails the doctrine of immortality for the righteous. The NRSV, however, basing itself on the LXX [Greek Septuagint], translates, 'the righteous find refuge in their integrity (betummo),' a reading that does not teach that doctrine.” It all depends on whether the original consonantal text read bmtw or btmw.

Commentators are divided on this point with Walls, for example, stating “AV may be right.” However, P.S. Johnston points out, “Such a refuge [at the point of death] is not otherwise an OT concept and is more in line with later eschatology (cf. Wis. 4:7-14).”

Proverbs 14:33b

There is a similar division of opinion regarding the text of this verse. The second line reads in the Hebrew: “(Wisdom) is known in the heart of a fool.” This does not appear to make much sense. However, the same Hebrew text can also be translated as “Wisdom is even known in the heart of a fool.” Hulst also offers another possibility, i.e. the verb yada may mean “humiliate” instead of “is known.” And Martin says that if the Hebrew wording is adopted, “the couplet is an expansion, not a comparison. Even among fools wisdom cannot fail to be recognized.”

But there is yet another explanation, i.e. the negative particle may have been accidentally dropped from the Hebrew text. Thus, it should read “not known” in place of “known.” Scott adopts this explanation in his Anchor Bible translation, and so does NRSV, which additionally notes that this is the reading in the early Greek and Aramaic translations of the OT. In favor of this possibility is the fact earlier mentioned in conjunction with verse 17; it would yield another example of antithetic parallelism:

“Wisdom is at home in the mind of one who has understanding,

but it is not known in the heart of fools.” (NRSV)

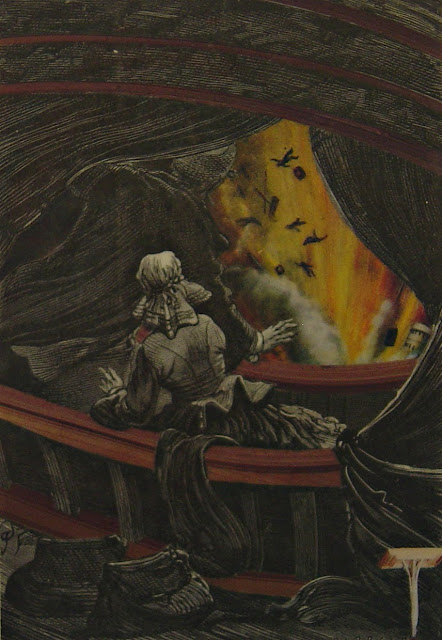

Finally, for a change of pace, consider this collage of mine based on the imagery found in this chapter: You might see how many of the images you can match up with the appropriate verse.

Proverbs 14 (1994)