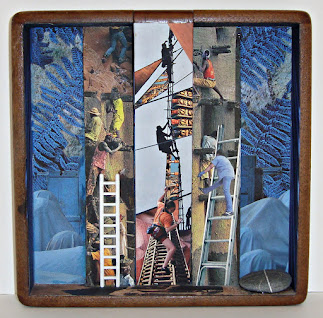

All Decked Out (2009 collage)

My comments here rely heavily on those of R.P. Gordon. We have two descriptions of God's commands regarding the proper attire for the priests to wear while officiating in the tabernacle. Chapter 28 outlines the requirements while chapter 39 explains that these instructions were all carried. Gordon remarks regarding Exodus 39: “The divergences from ch. 28 are few in number and usually of no great significance. The punctiliousness with which the earlier directions were observed is emphasized in the seven occurrences of 'as the LORD commanded Moses' (1,5,7,21,26,29,31).” This is an appropriate number of repetitions since 'seven' throughout the Bible denotes perfection or completion.

Exodus 28:1-5

In these verses “we find that holiness and beauty are not incompatible.” And this is especially true considering the materials utilized are to consist of “gold, blue, purple, and crimson yarns, and fine linen.” (Gordon)

According to later commentary in the Talmud, the length of the sash was calculated to be 48 feet. If accurate, this is too excessive for the NIV translation of “girdle.” We don't really know which it is since the rare Hebrew word only appears again in Exodus 28:39 and Isaiah 22:21. However, we do know from the latter verse that it is associated with a royal official of high standing.

Exodus 28:6-8

Gordon says this about the priest's ephod, “Opinion is divided as to whether the ephod was a waistcoat or a loin-cloth. On the basis of 2 Sam. 6:14,20 (David's immodest display when 'girded with a linen ephod') it might be concluded that it is the latter.”

Exodus 28:9-14

“Affixed to the shoulder straps of the ephod were two onyx stones in gold filigree setting.” The names of the 12 tribes were engraved on the stones. “Thus was symbolized the high priestly intercession on behalf of the individual tribes of Israel.” (Gordon)

Exodus 28:15-30

Quite detailed instructions are laid out concerning the breastpiece of judgment, which appears to be a large pocket containing the mysterious Urim (“lights”) and Thummin (“perfections”) used to determine God's will on a given subject by drawing lots or casting stones to answer yes-no questions. More concerning this process is discussed in my two posts titled “Judges 20:8-11 Urim and Thummin” and “Book of Judges: Questions and Answers.”

Exodus 28:31-32

Over the ephod went a violet-blue robe such as people of high rank wore. See I Samuel 18:4 and Ezekiel 26:16.

Exodus 28:33-35

These verses describe the decoration of the lower hem with alternating pomegranates and bells.

Regarding the bells, Gordon says, “They had more than a decorative significance,” and cites Cassuto as saying “Propriety demands that the entry should be proceeded by an announcement, and the priest should be careful not to go into the sanctuary irreverently.” Basically, as Sanderson puts it, “The bells will identify the high priest so that he may not die when he enters or leaves the holy place.”

Francis Schaeffer finds significance in the color of the pomegranates, as he explains in his enlightening pamphlet Art & the Bible: “Thus, when the priest went into the Holy of Holies, he was to take with him on his garments a representation of nature, carrying that representation into the presence of God. Surely this is the very antithesis of a command against works of art. But there is something further to note here. In nature, pomegranates are red, but these pomegranates were to be blue, purple and scarlet. Purple and scarlet could be natural changes in the growth of a pomegranate. But blue is not. The implication is that there is freedom to make something which gets its impetus from nature but can be different from it and it too can be brought into the presence of God.” Thus non-representational art is hereby sanctioned.

Exodus 28:36-39

The priest's turban was to have a plate decorated with a flower, blossom, or rosette. Gordon states, “ritual exactitude is enjoined so that the people's offering, as presented by the high priest, may be acceptable. The plate with its inscription in sacred characters would serve to compensate for any infringement of the ritual requirements such as the high priest might commit in the course of his duties.”

Exodus 28:40-43

The chapter concludes with the much simpler instructions regarding the attire for all of the priesthood.

Meaning

All of the above is merely of historical interest unless we see the underlying symbolic meaning of the vestments. And much of which we can learn actually comes not only from OT scholars, but also NT commentators, especially on the Book of Revelation where some of the Exodus imagery recurs in the description of the New Jerusalem.

The Dictionary of Biblical Imagery explains, “In ancient culture the blue, purple and scarlet suggested wealth and royalty...Blue, purple and scarlet colored the tabernacle of ancient Israel, suggesting that Yahweh was the wealthy and powerful God-king, who brought an impoverished people out of slavery in Egypt to make them a mighty nation...Blue was the dominant color of the vestments of ancient Israel's high priest (Ex 28)...He was the boundary between the human and divine realms [such as the blue sky], moving in both as he ministered in the Holy of Holies.”

Stibbs states that “in certain actions the priest represents the whole nation before God. The garments of the high priest symbolize this. Both the shoulder-pieces and the breastplate bear the names of the twelve tribes of Israel...It is as if Israel was acting in and through the actions of the priest...The distinction between substitution and representation is important for understanding the relationship between the priests and Levites and the rest of Israel. The priests do not undercut the calling of all the people to be a priestly kingdom, but to represent it. And as the priest is to the people, so Israel (ideally) to the nations.”

In this regard, keep in mind the words in I Peter 2:4-5 addressed to the early Christians: “Come to him, a living stone, though rejected by mortals yet chosen and precious in God's sight, and like living stones, let yourselves be built into a spiritual house, to be a holy priesthood, to offer spiritual sacrifices acceptable to God through Jesus Christ.” (NRSV)

H.R. Jones says, “The high priest and every other priest acted as intermediates between the people and God for such purposes...The ministry of the high priest adumbrated that of the Lord Jesus Christ (Heb. 7:1-10:39).”

“The jewels in the breastplate of Aaron represented the various tribes. Tribal unity is the foundation of the new city; cf. Rev 7:4-8.” (Ford)

“Although in a different order, the names of the precious stones in Rev. 21 closely resemble those on the high priest's breastplate in Exod. 28:17-20...Bousset shows that the variations between Revelation and Exodus can be explained, so we may safely assume that John intended to reproduce the OT list. But Bousset is unable to account for the order of the stones, which in fact differs widely in all the lists (Exod. 28; Ezek. 28MT; and ibid., LXX).” (Hillyer)

Jacques Ellul, after rejecting some of the many explanations over the years regarding the symbolism of the individual stones and the Urim and Thummin, concludes: “We must not forget that the breastplate belonged to the high priest. The stones are found in the city [i.e. New Jerusalem] because they represent what the high priest bore. They decorate the city, as once they adorned the high priest. They are hidden in the foundations of the wall, as they were once hidden in the mysterious pocket from which came the oracle of God's Word. They are present in the city to tell us that the high priest's office has been accomplished and brought to perfection.”